Crows memorize human faces. Orcas express mourning. And that cockroach that skittered across your kitchen counter the other day? According to researchers in Belgium, that little fellow might have been shy or outgoing.

Recent revelations about the emotionally complex lives of many species have only been made possible by growing research on animal behavior and personality. This has led scientists like Dr. Shifra Goldenberg, an ecologist at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute’s Conservation Ecology Center, to embark on “conservation behavior” as a focus of her work. Conservation behavior describes how experts like Dr. Goldenberg are seeking to better understand how animal decision-making and personality come into play in human-dominated landscapes.

After all, what “wild” increasingly means isn’t pristine habitat, with less terrain on the planet truly untouched by people than ever before. Getting insight into not just how animals relate to each other, but also how they relate to us, and the spaces we dominate, might be essential to their preservation.

And now Conservation Nation has joined the broader movement to better understand animal personality by funding a Smithsonian-led pachyderm project led by Dr. Goldenberg. While elephants have long been a source of fascination for behavioral study, this two-part project intersects personality testing with conservation efforts by focusing on a unique group: Asian elephants in Myanmar who have been “unemployed,” but still live in former logging camps and roam the forest at night.

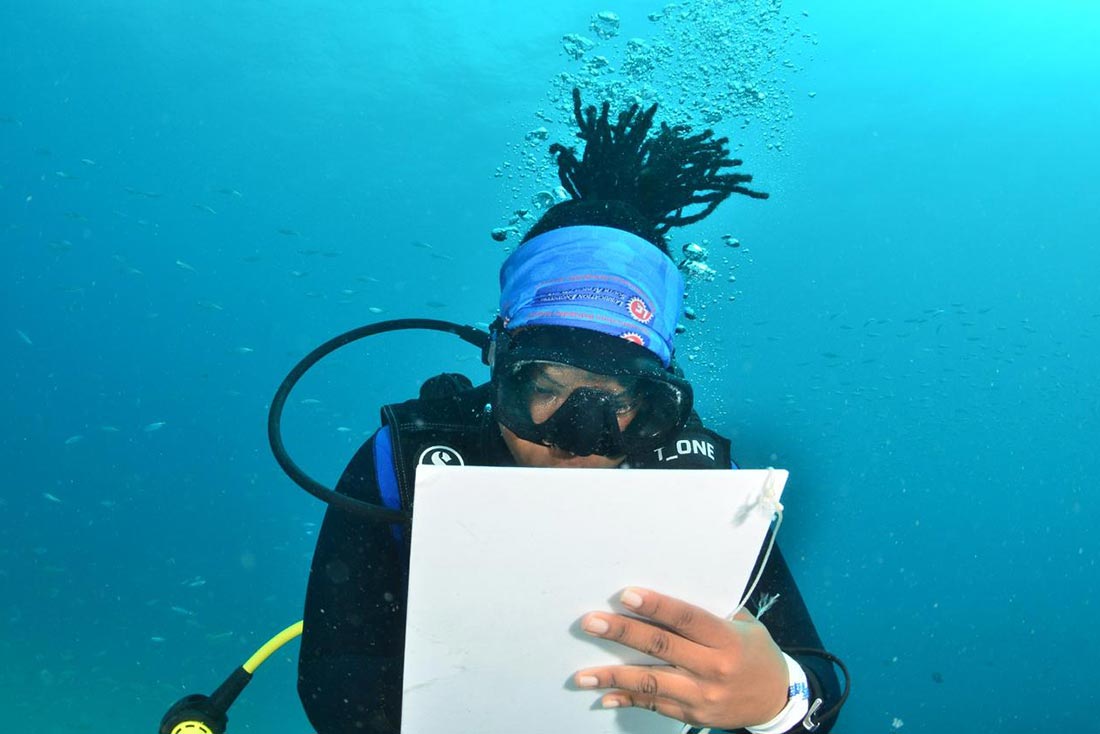

For the first part of the study conducted earlier this year, a graduate student at Hunter College-CUNY, Sateesh Venkatesh, gauged whether elephants differ from one another in their response to novel objects by testing 31 elephants with specially designed puzzles.

They suspect certain personality traits revealed by individuals during the test, paired with tracking data of elephants moving around the landscape, might be related to their interaction with people. For example, elephants who displayed boldness while completing the test might be more likely to trespass into farmland and villages. With elephant-human conflict on the rise, those brave elephants more likely to venture into human areas—and less likely to fear people in general—would not be suited for rewilding.

The second part of the study is ongoing. Together, Sateesh and another graduate student at Colorado State University, Aung Chan, will track the elephants’ nighttime treks using GPS to record whether they enter populated zones. Then, the researchers can compare the data, assessing whether there is a correlation between the animals’ personality type and their decisions about where to roam at night. With these data streams compared, the study’s findings could be an important step forward in understanding elephant behavior, paving the way for conservation and rewilding efforts carefully tailored to an understanding of the species.

Look for more updates about this project in 2020, after the second part of the study is complete.