The Guam kingfisher is extinct in the wild. For now. Scientists hoping to rewild the species need to launch a study gathering key information about how they can successfully breed these birds. Kingfishers can be difficult to match with a mate, so by learning more about the species’ hormones, they will be better able to encourage successful pairings. That way, they can bolster the population with a new generation of chicks, reintroducing a flock to the wild within the next few years.

Why are Guam kingfishers in trouble?

Known as “sihek” in their native habitat, Guam kingfishers no longer live in the wild. That’s because a predator, the brown tree snake, was introduced in the 1950s and has killed many animal populations native to Guam. With efforts underway to contain this invasive snake species, conservationists and scientists have the remaining kingfishers at research facilities. To introduce a new generation of Guam kingfishers to their original habitat, researchers need these critically endangered birds to breed in human care. But getting them to mate has proven to be no easy feat, as potential pairs can be aggressive during introductions.

What exactly is being done to help and where?

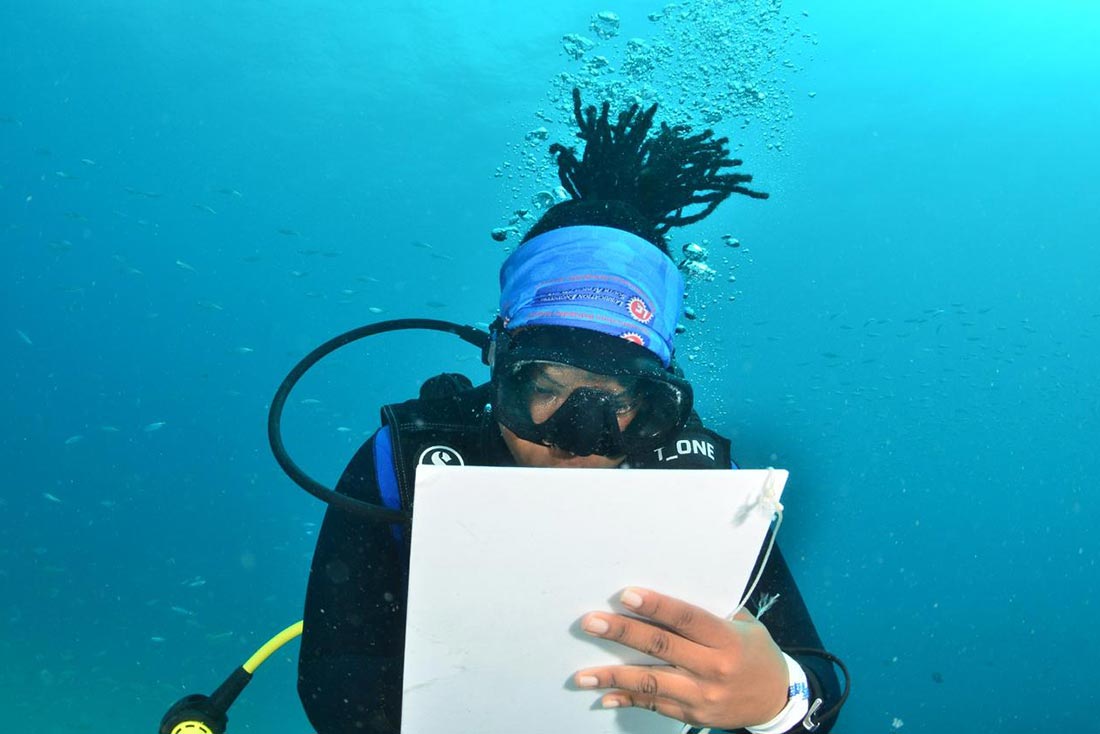

Experts need to know how to best pair these kingfishers so they can produce healthy chicks and reintroduce the species in the wild. Other bird species have exhibited a hormonal increase during successful introductions. Scientists want to know if there are endocrine patterns or early cues that can indicate compatibility for Guam kingfishers, too. They needed Conservation Nation’s funding to analyze fecal samples from these birds during the introduction of three new potential breeding pairs to provide us with clues to help these critically endangered birds reproduce and thrive.

What specific items or support do scientists need to make this possible?

We funded the endocrine analysis at the SCBI Endocrinology Lab and supported an undergraduate intern who assisted scientists in this project.

If this early endocrine signal exists, this method could be used to screen pairings early and speed up the process to better facilitate breeding. This project is an important step toward reintroducing the species to the wild as early as 2021.