In 2017, scientists tagged 11 reticulated giraffes with high-tech, solar-powered, satellite transmitters. Just months later, the information gathered revealed a sobering reality—four of the animals had been poached.

And for this giraffe, primarily found in Kenya’s arid plains, poaching isn’t the only – or even primary – danger. Like so many wild animals across the globe impacted by human development, giraffe populations have fallen by 30 percent in the last three decades, largely because of land fragmentation and fencing. Habitats are increasingly determined not by where resources or migratory patterns are, but, rather, by where humans are not.

“We’ve never been able to track giraffes for long periods. It’s partly due to the animal’s morphology,” says Smithsonian scientist Dr. Jared Stabach, a lead researcher on the project.

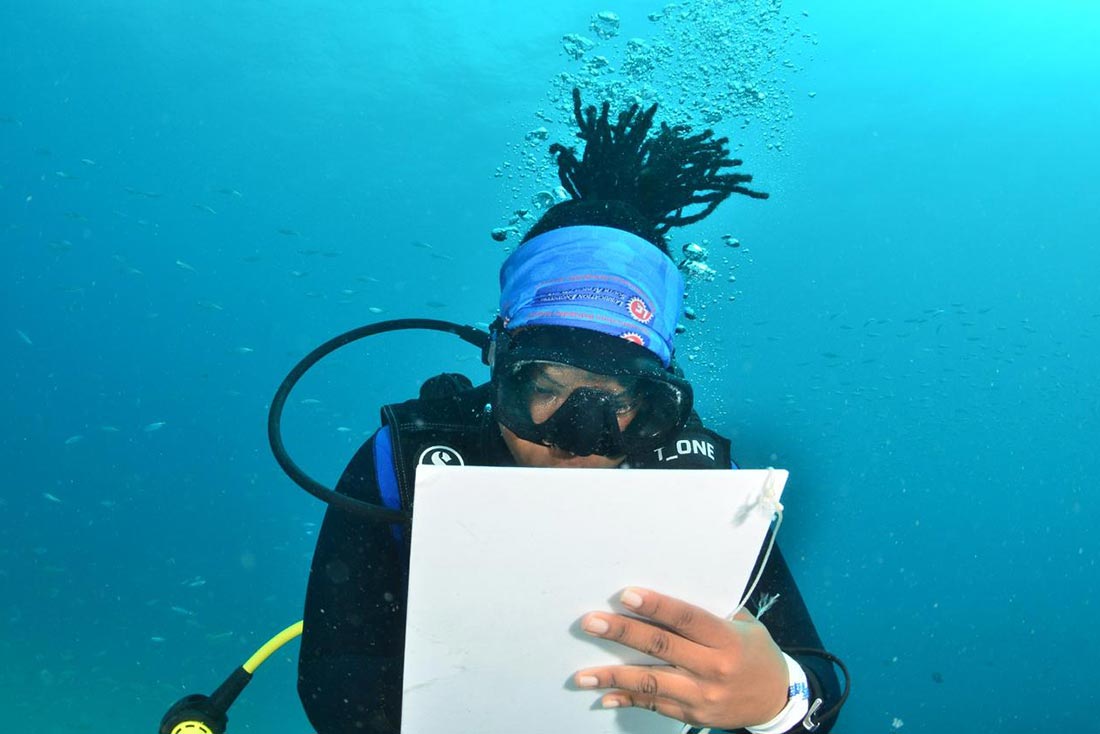

In the past, Dr. Stabach explains, conventional collars were used to middling effect, thanks to giraffes’ famously long necks. This led researchers to design a new model, which attaches to the “ossicone,” the hornlike protrusions on top of a giraffe’s head, providing a much more reliable transmission of data from the animal’s highest point. Data are being collected every hour of every day. These devices also are solar powered, extremely lightweight, at just 180 grams, and can last for up to 2-4 years.

Conservation Nation partially funded the tracking effort by purchasing five of these transmitters, and by supporting the team’s challenging work in the field. “These collaring activities are risky,” Dr. Stabach says, adding that a wild giraffe has to be safely sedated for the transmitter to be correctly placed.

Even with the risks in mind, and even when the study endures tragic setbacks like animals lost to poaching, this research is key for the future of the species in the area. Already, a pipeline project is planned to extend across the region. If researchers can get the most comprehensive data, they can work with local communities and the Kenyan government to influence the project, perhaps even to shift the pipeline’s path, so as to impact these struggling creatures the least.

And that’s why, Dr. Stabach says, expanding the sample size for the study is crucial. The collaborators leading the project, which includes the Giraffe Conservation Foundation and San Diego Zoo Global, hope to get substantial information about another 20-30 animals to provide a more comprehensive view of the spatial ecology of the species across the region. This past August, they finished another expedition in the area, which included safely tagging 28 new participants in the study. This represents the largest tracking study on any species of giraffe ever conducted and an important step towards an increased understanding of the species.