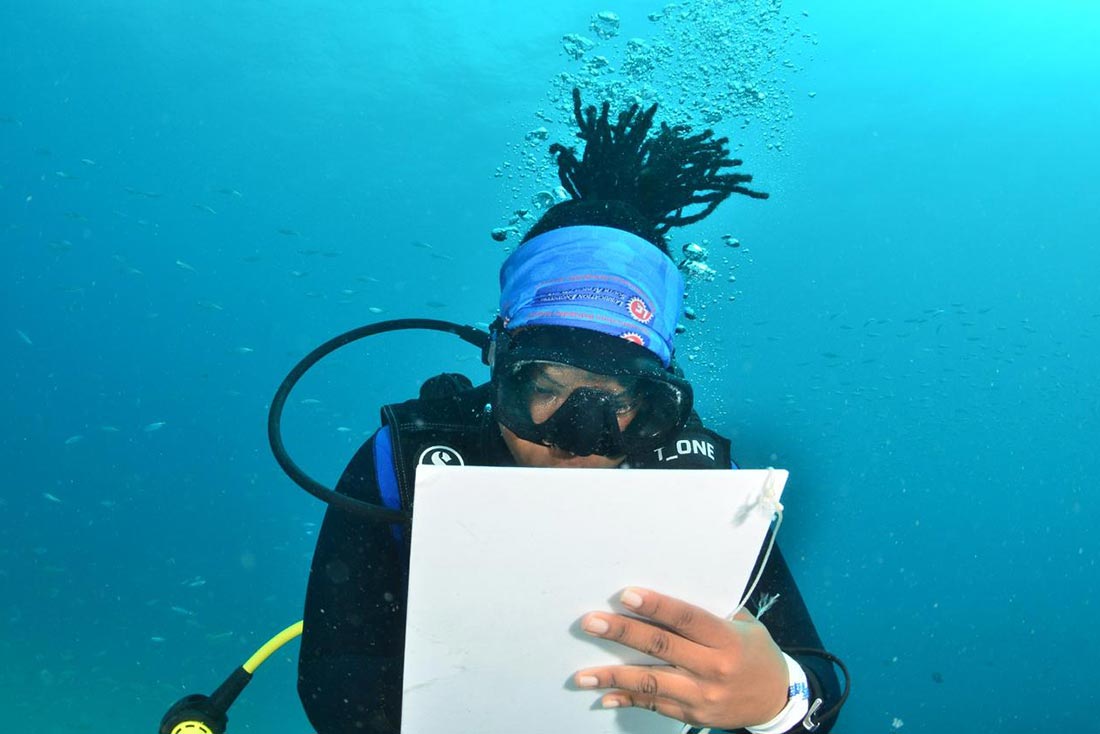

Eight of Conservation Nation’s wildlife projects have included the purchase of high-tech tracking equipment. And that’s just us. Trackers are everywhere—being used in studies on animals ranging from urban coyotes to invasive insects.

So, why the tracking craze? The data gathered has led to revelations about population sizes, animal movements and, crucially, about how endangered species are impacted by people.

That’s why it’s so important for conservationists to know about even seemingly small obstacles to animal movement. They need to better understand how animals are coping with challenges like raised land, reduced access to water and habitat segmentation. By following a single creature, we learn how to protect it, and by extension, how we can save its whole species. In some cases, we can even learn how we might better preserve entire ecosystems, working with local governments and landowners to enact wildlife-friendly policies impacting countless species.

A study of giraffes in Kenya is an example of how this technology can be essential to conservation efforts. To support scientists at the Smithsonian’s Conservation Biology Institute, Conservation Nation purchased five solar-powered GPS prototype trackers. The prototypes were designed to fit on one of a giraffe’s ossicones (the two hornlike protrusions on top of a giraffe’s head). With the data gathered, scientists learned that in 2019 alone, four of the studied giraffes had been poached. It turned out herds were moving across private lands—instead of protected lands—and were more vulnerable to hunters.

Of course, it’s not easy to implement change, even once we know how animals are faring in the wild. But with meaningful data, Smithsonian scientists can work with local communities to plan land development more thoughtfully. They can focus their efforts on specific communities, educating and supporting those who might poach because intense poverty has led them to feel they have no other choice. In some cases, they can offer compensation if animals like cougars or wolves eat farmers’ livestock—preventing those farmers from needlessly killing these endangered predators. Collaborating with governments and landowners, they can establish “wildlife corridors” through private lands, preserving natural migratory patterns.

Even with the benefits of tracking information, researchers have seen the technology’s downside, too; poachers have, in some cases, successfully hacked conservationists’ signals to track endangered animals, leading to increased calls for the encryption and protection of location data.

Results aren’t always so bleak.

There have been reports of conservationists embedding GPS trackers into rhino horns, so if animals are tragically poached, authorities will at least have a way to find those who take the horns.

And in 2017, Conservation Nation purchased high-tech, solar-powered transmitters to track six pelicans along the Chesapeake Bay. The species’ numbers had plummeted due to pesticide use, but since that pesticide was banned, a resurgent pelican population was found nesting on marshy islands along the bay. Scientists were then able to trace the birds’ unique paths as they migrated, registering their stops to perch on manmade structures like factories and power plants, even as they ventured as far south as Cuba. With these insights, they collaborated with researchers in North Carolina, comparing data that could lead to new policies encouraging population growth across states.

Autumn-Lynn Harrison is a Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center research ecologist. In 2018, she saw the population thriving firsthand, and said being able to track its movements with high-tech tags was invaluable. “Seeing so many birds nesting on the islands illustrated just how much progress we have made toward the recovery of this species, and of the Bay.”

And as trackers get smaller and better adapted to different animals’ physiology, results will only improve. Newer, lighter trackers are less likely to fall off, encumber the animal or impact its behavior. Just last year, Conservation Nation funded tracker technology for projects focusing on eastern meadowlarks in North America and Lowland tapirs in Paraguay. With the results from these studies and others like it, we will be better equipped to protect wildlife and the habitats they call home.