To apply sunscreen or not to apply sunscreen—that is the question. And for many of the conservation-minded, the answer can be complicated. According to the National Park Service, 6,000 tons of sunscreen are likely washing off beachgoers and harming coral reefs yearly.

The problem is so widespread that this past month the House of Representatives voted to approve a bipartisan bill to restrict the use of certain sunscreens in parts of Florida, protecting nearby reefs. The city of Key West, Florida approved a ban earlier this year, as has Hawaii.

Why does sunscreen hurt coral?

Active ingredients oxybenzone and octinoxate contribute to reef “bleaching.” And it’s not just coral—ingredients in sunscreen are toxic to fish and other marine life, too. According to the Ocean Foundation, these minerals “catalyze the production of hydrogen peroxide, a well-known bleaching agent, at a concentration high enough to harm coastal marine organisms.”

Many visit these areas because they love nature—and yet are inadvertently contributing to its decline by simply trying to be safe in the sun.

Is there a kind of sunscreen you can purchase that will not harm marine life?

There are reef-safe sunscreens that eco-friendly retailers, such as REI, have begun to offer. Unfortunately, studies still show these less harmful options likely still impact marine ecosystems negatively. And many of the products on the market haven’t been confirmed by scientists as truly reef-safe.

Another way to stay protected from the sun without poisoning the ocean? Cover up—by wearing clothing that has an ultraviolet protection factor, you can drastically reduce your sunscreen use.

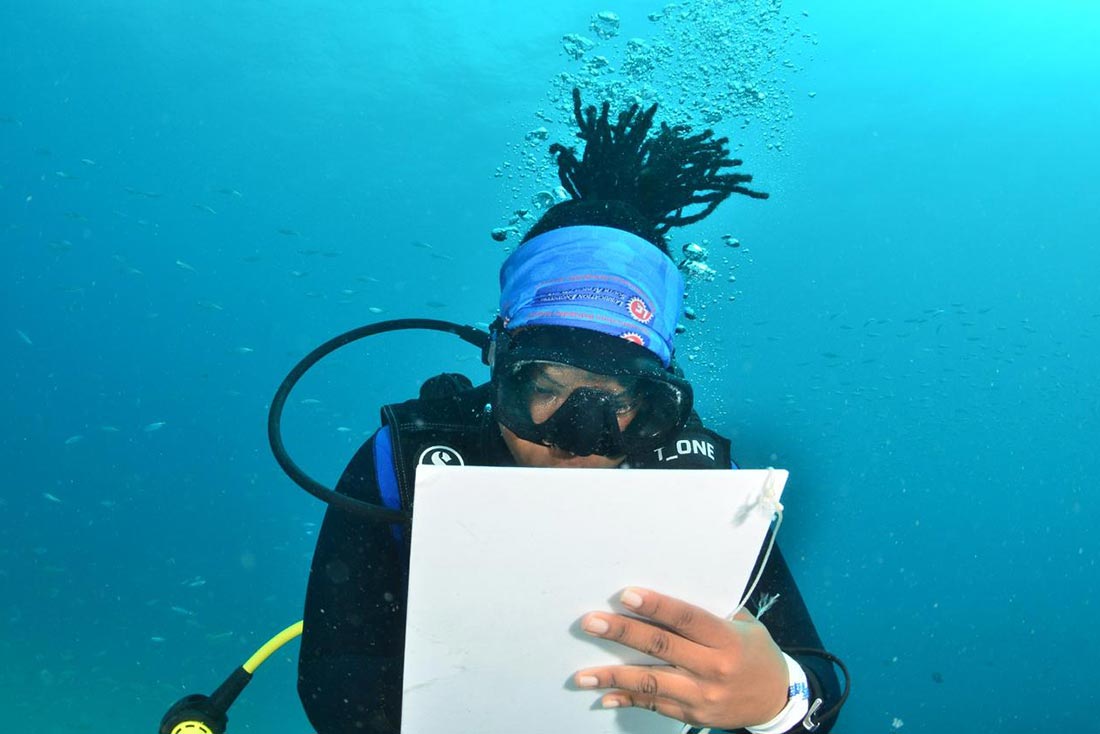

What is being done to protect coral species?

Scientists at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute have been at the forefront of coral research. Not only have they been able to breed coral from different regions, strengthening species fading in the wild as the oceans warm, but they also have cryogenically frozen and preserved endangered coral populations.

This means that should coral in the wild die out, there will be a repository of species that can be used to repopulate our oceans. Learn more about the Smithsonian’s groundbreaking work saving coral here.