Amid the ongoing loss of wildlife habitat, large carnivores are being pushed to human-dominated areas, affecting their behavior and health. Ecosystem and public health are tightly linked so this increased overlap between carnivores like pumas, domestic animals, and people raises concerns about disease transmission between these groups. This is of concern in California, where pumas are the only apex predator left in most of the state. Their habitat is subject to intense encroachment from human activity like urban development, roads, and outdoor recreation. The San Francisco Bay Area’s puma population is threatened with extinction due to habitat isolation and they’re listed as candidate Endangered species under the California Endangered Species Act due to early signs of inbreeding and reduced genetic diversity.

Most (>70%) diseases are zoonotic in origin, meaning they can be transmitted between people and animals. The urgency to monitor wildlife health is increasingly clear, as shown by recent outbreaks of Avian Influenza in the U.S. A growing body of research shows that species in and near urban areas are more prone to disease and have compromised health, but the understanding of the long-term impacts of urbanization on wildlife health remains limited. That affects our ability to predict the impacts on human-wildlife conflict and public health.

With support from Conservation Nation, Felidae Conservation Fund is monitoring the impacts of urbanization on puma and bobcat health in the San Fransisco Bay Area as part of a five year project to non-invasively collect wild cat health data. In particular, we’re interested in the North Bay Area which appears to have abundant prey and an extensive protected area network. However, puma activity seems lower than expected and it’s not clear how animal health is affected in this multi-use landscape.

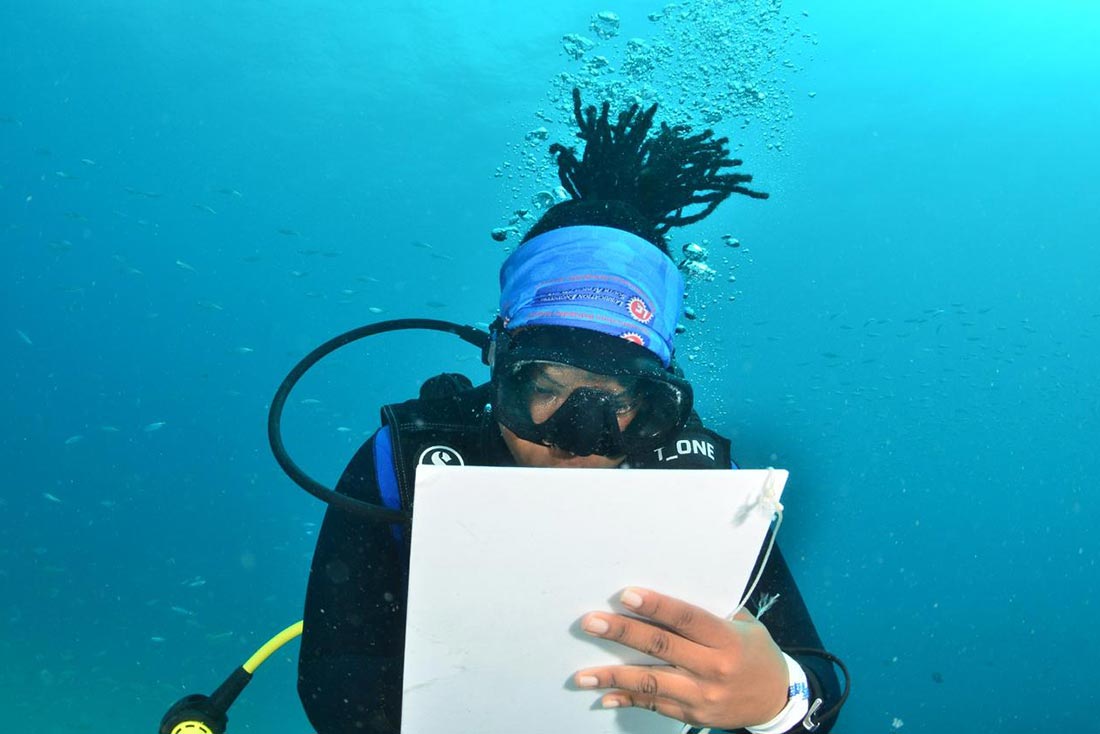

For this project, we are using camera traps to monitor animal habitat use and scat (i.e. feces) surveys to measure animal health. We have cameras across the Bay Area and data we get from the images helps us understand puma habitat use across the area and how it varies with human footprint. Our camera trap efforts also help prioritize areas to search for puma and bobcat scat . Scat can tell us about animal health and we can extract DNA from samples, which helps to determine population numbers. To find scat we used a detection dog named DJ. We made sure to start our work at sunrise in order to finish our search times before the day got too hot for DJ (and us!).

After our three week survey across the Bay Area, we sent our samples to our partner labs for analysis of various health markers. We’re especially interested in measuring puma exposure to diseases caused by parasites like Toxoplasma gondii because they can be transmitted between people, wild cats, and domestic species. Toxoplasma gondii increases host dopamine levels and alters host behavior. For domestic cats, this may lead to riskier host behavior and for wild cats it may make them more aggressive or less afraid of people, contributing to human-wildlife conflict (e.g. attacks on pets).

We’re also testing samples for exposure to mercury and stress hormone levels in urban areas which can compromise immune systems and is of concern for populations with low genetic diversity such as pumas in the Bay Area. Together, this will help to fill in important gaps about where disease exposure is more likely for wild cats and how that relates to proximity to urban areas or protected area edges.

We’re still awaiting the results of our 2024 survey, where we collected almost 200 samples. We expect to see greater evidence of parasites, pollutants, and stress in samples collected closer to urban areas. While we still have much to learn about wild cat health at the urban edge, we hope the long-term dataset of puma and bobcat health we are building with our data collection will shed new light on the strong interconnectedness of wildlife, domestic animal, and human health.