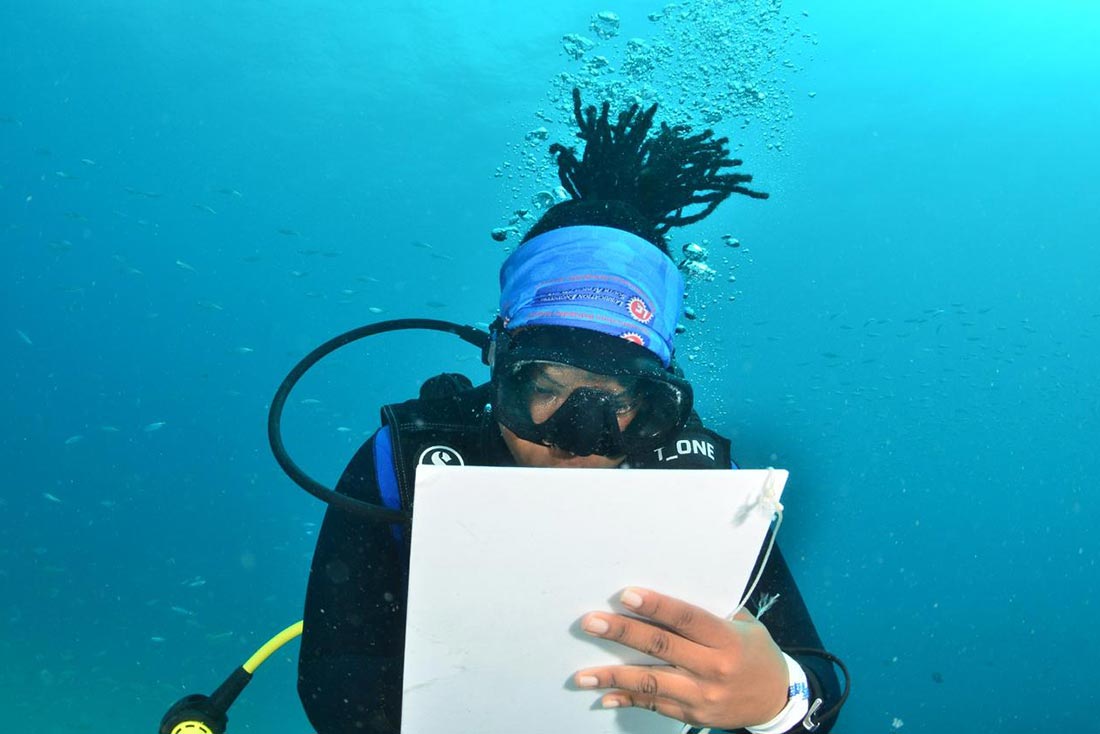

I recently returned from conducting fieldwork in a place that few people get to visit: Antarctica. As a graduate student at Montana State University, I was stationed at McMurdo Station to collect data for the Weddell Seal Project—a fifty-year-long, capture-mark-recapture study focused on Weddell seals in Erebus Bay. The project’s backbone is straightforward: (a) individually mark every seal in the study area using simple plastic livestock tags and (b) record every seal encountered during resight surveys each year. Simple enough, but the data collected are rich. Knowing ages, reproductive histories, and abundance estimates for this population across decades can help us answer endless questions with the dataset. To continue maintaining this database means spending just over two months in Antarctica annually.

Working in Antarctica is a unique experience. Our six-person team flies to New Zealand in October before boarding a military-grade C-17 to fly down to “The Ice.” We arrive at McMurdo Station with hundreds of support staff as the station gears up for the busy science months of the Antarctic spring and summer. It’s around this time that Weddell seals, known for their incredible breath-holding capacity, swim under miles of frozen ocean to arrive at the pupping colonies near McMurdo Station. We access the eight to fourteen colonies that form each year by driving snowmobiles on the sea ice, and spend the next two months tagging and recording seals in the study area. In recent years, we have tagged over 500 pups and over 100 adults in a single season.

I frequently get asked how I stay warm in Antarctica during my six to ten hours in the field—it comes down to lots and lots of layers! Don’t get me wrong, on days when it’s below zero degrees Fahrenheit, and we’re yelling to hear each other over the “breeze,” I want to head home to get warm. But generally speaking, I love working down there. The scenery is stunning, the seals are entertaining and docile, and the support is unparalleled. McMurdo Station exemplifies the adage: it takes a village. From the chefs who ensure we get fed to the mechanics that fix the snowmobiles when they break, it takes many people to make a field season happen. This supportive and collaborative spirit is something I try to exemplify throughout my life.

In addition to McMurdo Station being a unique and supportive environment, it is also an excellent area for research. Our study population of Weddell seals sits at the world’s southernmost site for a breeding mammal and is at the southern edge of the species’ range. These animals rely on the productive and understudied Ross Sea in the Southern Ocean and its annual sea ice for survival and breeding. As the oceans warm and the sea ice changes, it is unclear what will happen to this long-lived species. But, while we do not know the future, having more than fifty years of historical data on this population will provide us with an unparalleled opportunity to investigate the factors that impact these seals and information about their life history. My interests lie in understanding a small part of these topics: researching how many pups are born each year and why.

With the field season complete, I can shift my focus to processing and analyzing the data to dig into this question. I look forward to sharing my journey with the Conservation Nation community.