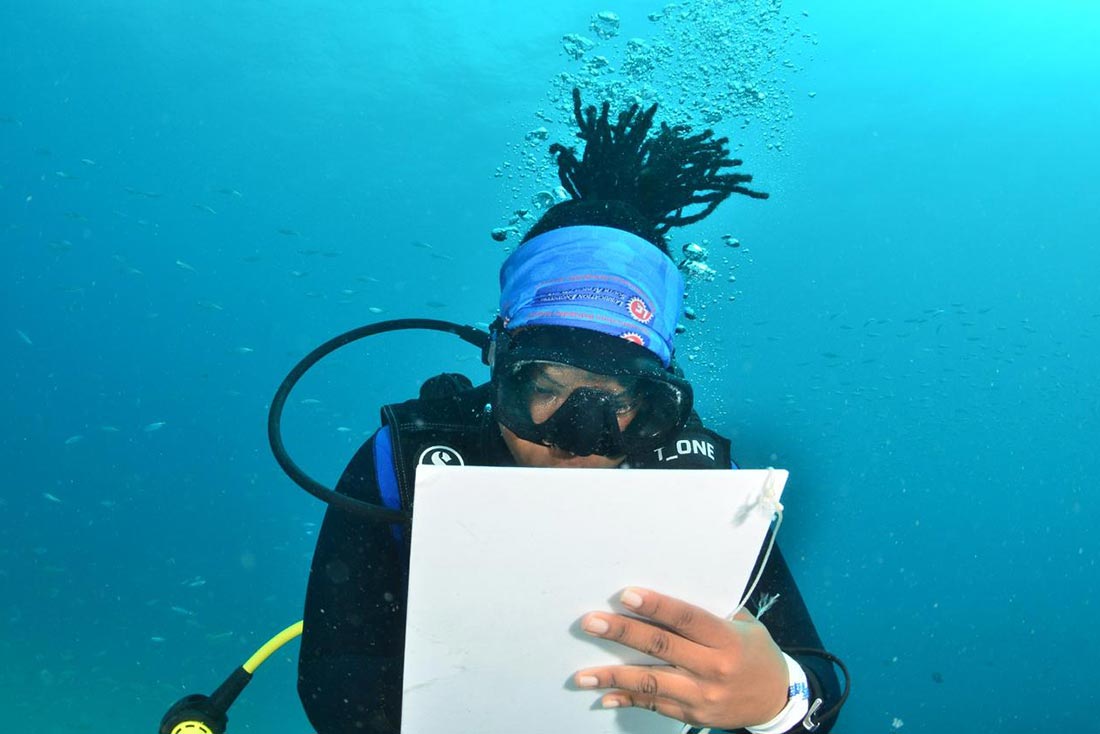

Last summer, I spent over two months conducting the exploratory assessment phase of my dissertation research in the Loreto region of the northern Peruvian Amazon. I designed my study to help understand and address the urgent and complex social and ecological issues that riverine (aka river-edge dwelling) communities face—especially the struggle to develop and enact more effective policies and community-based sustainable management initiatives to conserve freshwater ecosystems.

I launched into this initial phase of my research with three goals in mind: to familiarize myself with the local context and the stakeholders involved in relevant activities (such as artisanal fisheries) in the region; to build local connections and explore potential collaborations with professionals, organizations, and local government representatives working on similar issues in Loreto; and to conduct interviews with key informants to gather information for a policy analysis case study focusing on fisheries regulations in the Peruvian Amazon.

Throughout my assessment, I enjoyed various advantages as a Peruvian citizen—including inclusive attitudes and behaviors from local citizens toward my research. These factors helped establish good relationships with community members, who saw me as a fellow local (aka “charapa”) and were eager to connect over our common Amazonian roots. The fact that I spoke native Spanish further enabled me to immerse myself in the Loreto culture and facilitate my activities and interactions with local stakeholders.

I also found it beneficial to my project to participate in community events to learn about the culture of Loreto, connect with locals (including members of the regional government), and immerse myself in the lives of local people. One notable event I attended was the San Juan celebration. At this festivity, all Amazonian regions come together to eat and celebrate their identity while dancing and enjoying local delicacies, including juane—a traditional dish made of chicken, rice, eggs, and cilantro sauce wrapped in the leaf of the native bijao plant.

Of course, I also faced some challenges along the way. I experienced various scheduling constraints due to my assessment’s short time frame and found it difficult to gauge the length of travel to unfamiliar sites. I also struggled with technical issues, including low-quality wifi and a humidity-induced laptop failure. One of my biggest challenges was avoiding bias while conducting culture-centric research and interviewing locals. Being a local researcher poses unique difficulties in maintaining objectivity; I sometimes found it hard to separate my perceptions as a Peruvian and resident of the Amazon from my roles as an academic and scientist.

At the conclusion of my exploratory assessment, I successfully reached each of my goals. My fieldwork gave me a richer understanding of the area’s background, culture, and demographics. It also provided preliminary data suggesting that fisheries regulations in the Peruvian Amazon tend to exacerbate the condition of vulnerable populations. The results also imply that these policies are ineffective at closing the inequality gap for those who should benefit most from them—namely riparian Amazonian communities who depend on fisheries and freshwater ecosystems. I presented these findings at the 2022 Annual Meeting for Tropical Biology and Conservation in Cartagena, Colombia. I also compiled my results into a policy analysis case study called the Reglamento de Ordenamiento Pesquero de la Amazonia Peruana (aka Fishing Management Regulations for the Peruvian Amazon).