A Forest of Hope

I am sitting at a threshold, I am watching change. Last night, I laid down under trees that appear dead. I gaze through bare branches and the sounds of night are dominated by wind rustling through dry leaves. This morning, I awoke to new growth. With the first rains promising, the dry branches have miraculously sprouted new leaves and the croaking of frogs and chirping of crickets fills the air.

This is not the only change I am observing. From my seat on a boulder in a dry river bed, trees cloak the hillside to my right and the smell of the famous incense “palo santo” heavy in the air. To my left is a bare savannah, cleared of forest, interspersed with patches of bright green plantain farms where the air smells of moisture and mangos. This riverbed marks the border of the Salitral-Huarmaca Regional Protected Area, one of many efforts to protect the last primary growth Tumbesian dry-forest ecosystems in Peru. To prevent illegal loggers from turning this forest into a mirror image of the (western) bank, volunteer park guards patrol the entire area.

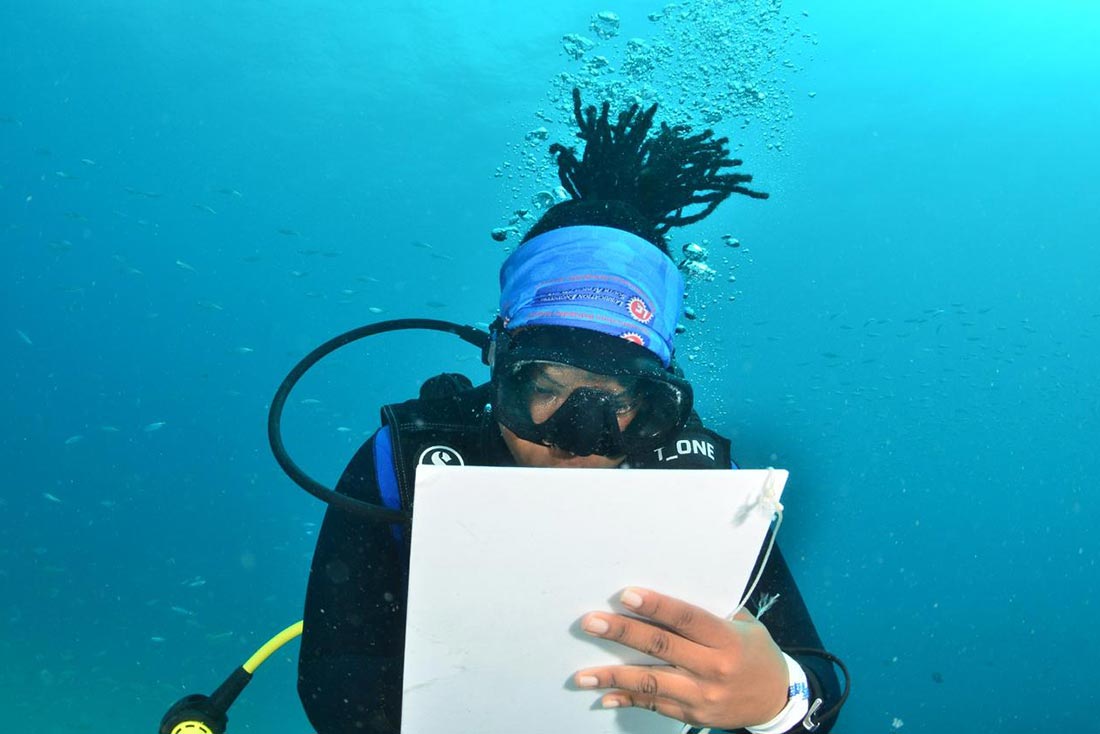

Researching and Defending Our Forgotten Foresters

In order to maximize seed dispersal by bats, we are working to understand their habitat use, diversity and movement across the landscape. With the help of funding from Conservation Nation, I spent a year traveling around northern Peru to study bats at 136 locations ranging from cloud forests, to cactus covered savannahs, from beach caves to university campuses, from waterfalls to cacao plantations. We captured over 5,000 bats belonging to 66 species across 9 protected areas and dozens of rural communities.

Abundance and Generosity

This was my first time working with bats outside of the United States and I was quickly humbled by the contrasts. By my second night, we had captured more species than exist in the State of Florida and by my second month, I had handled more bats than in three years of netting in the Eastern US.

Even more striking was the hospitality. From the first community meeting, people were fighting to have us sample in their farms or to be our guides into the forest. I sometimes had to take a deep breath before reminding the neighbors offering us free breakfast at 5:30 am that we finished work at 1:00 am the night before. I will be forever grateful to the school principals who lend us their office floors to sleep, to the volunteers who helped with digging out a road with machetes after a mudslide, and to the amazing biologists who founded and manage these conservation areas. As I settle into data analysis and modeling, long days will be fueled by the energy and generosity of everyone we met along the way. Results will help guide protected area development and land management.