To collect the poo, or not to collect the poo—that is the question. It is, anyway, for Smithsonian scientists in the midst of a conservation project focusing on microbes in cheetah scat, and culminating in a graduate student’s Conservation-Nation funded trip to Namibia in two months.

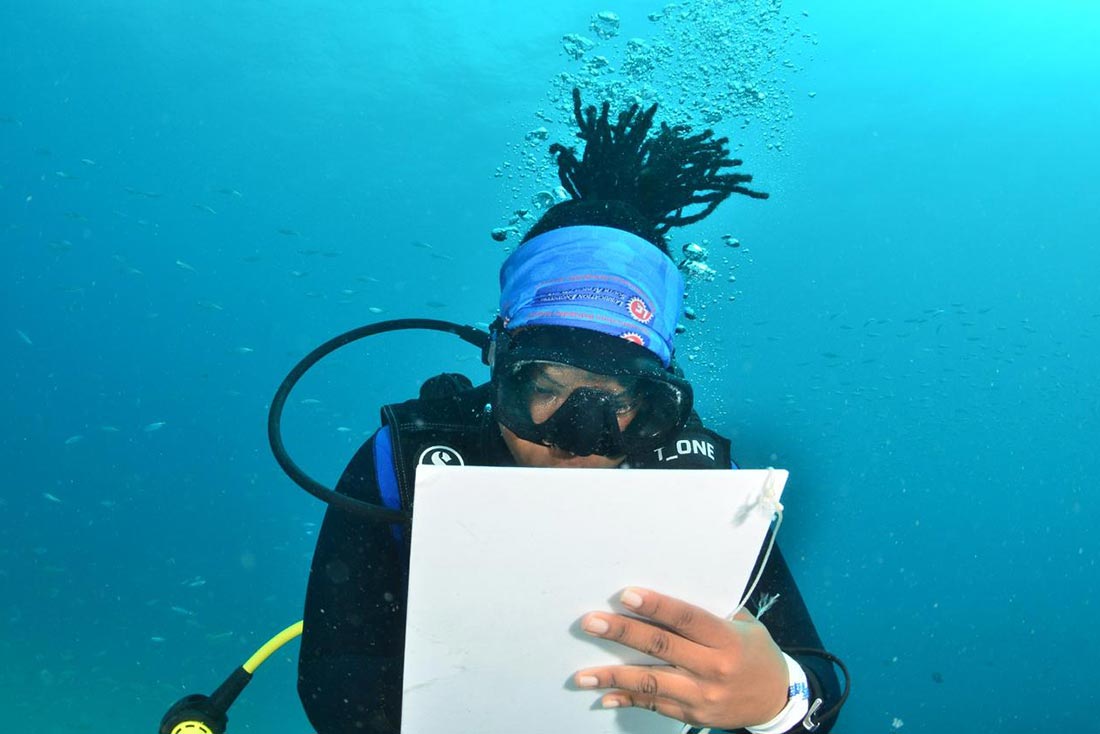

That PhD student, Morgan Maly, has been focused on cheetah poo—and all poo-related quandaries—for the better part of this year, as she has studied samples from cheetahs at research institutions, including the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) in Front Royal, Virginia.

Key to this project’s success leading up to its next stage in the field? Understanding that not all cheetah scat is created equal—from a testing standpoint, anyway. To help ensure the best data is collected moving forward, Morgan and the team launched a preliminary experiment to determine how long samples can still be analyzed for microbial content after leaving a cheetah’s body. An hour, they wondered? A day? A week?

“If we wait too long to collect the sample, it may contain more environmental microbes than the microbes from the actual cheetah,” said Dr. Adrienne Crosier, cheetah curator & research biologist at SCBI.

After an experiment comparing the samples of eight cheetahs, the team have their answer: 48 hours. That means when Morgan’s in the field in two months studying wild scat, she’ll be better prepared to answer the (time-honored?) question of whether to collect the poo, or not to collect the poo.

This kind of preliminary work is a great example of just how much researchers have to do to prepare for any variables that might influence their results—often, those in the field have precious time to gather critical data.

Stay tuned for updates about the project, which will continue into 2020 as the team studies the samples Morgan gathers in Namibia to better understand vulnerable cheetahs’ diets.