Project Background

Vohibe is a rainforest on the edge of a remote forest corridor in Madagascar. This region is accessible via a day-long riverboat journey and hours of hiking through hilly landscapes of farmland and small rural villages. The Vohibe forest, managed by the local community, VOI Soavinala village association, and the Missouri Botanical Garden (MBG) Madagascar Program, harbors an astonishing diversity of plants and animals, including at least ten species of lemurs threatened with extinction. My work there started in 2021 as part of a project led by Washington University in St. Louis (WUSTL) with the support of the Living Earth Collaborative and the Eric P. and Evelyn E. Newman Foundation, and it is ongoing also thanks to the support of the Center for the Environment at WUSTL and Conservation Nation.

The main threats to Madagascar’s lemurs are hunting and habitat loss—the latter driven by deforestation for agriculture, logging, and mining. After a year in Vohibe working with Malagasy Ph.D. students and the local community on lemur conservation, I saw firsthand that, despite being a protected area allowing sustainable resource use in designated zones, the region still faces significant threats.

Our work with lemurs focuses on two critically endangered species: diademed sifakas (Propithecus diadema) and black-and-white ruffed lemurs (Varecia variegata). Why these species? We mainly selected them because they are on the brink of extinction and need to be monitored in areas where they have never been studied, like Vohibe. Before our research, there were few sites in Madagascar where researchers conducted long-term research on either species.

Drop, Scoop, and Grow: Lemurs and Humans Team Up for Forest Revival

Black and white ruffed lemurs are frugivores, meaning about 90% of their diet is fruit from different tree species. When they eat, fruit seeds pass right through them undigested. And guess where we find them? Yes! In the lemurs’ poop! Previous studies have shown that seeds that pass through black-and-white ruffed lemur digestive tracts have better germination rates. In fact, this digestive process is crucial for germination in some plant species.

The seed collector for my project, Paky, followed our focal lemur group and collected hundreds of seeds from their poop. She also collected seeds dispersed on the forest floor by trees. This project was Paky’s first experience working in conservation, and she loved it! Dimby, the plant nursery keeper, planted the seeds, kept track of germination, and cared for the seedlings until they were ready to be transplanted in degraded areas of Vohibe. On top of improving germination rates, our nursery planting process focused on the tree species lemurs feed on, thereby enhancing restoration efforts and habitat quality.

In June and July 2024, many local community members participated in our forest restoration events, planting over 600 seedlings in a fragmented and degraded section of Vohibe! Locals were very enthusiastic about this part of the project and expressed a strong interest in continuing it into the future (although sustaining these efforts will require ongoing support).

Documenting Lemurs’ Lives in the Forest

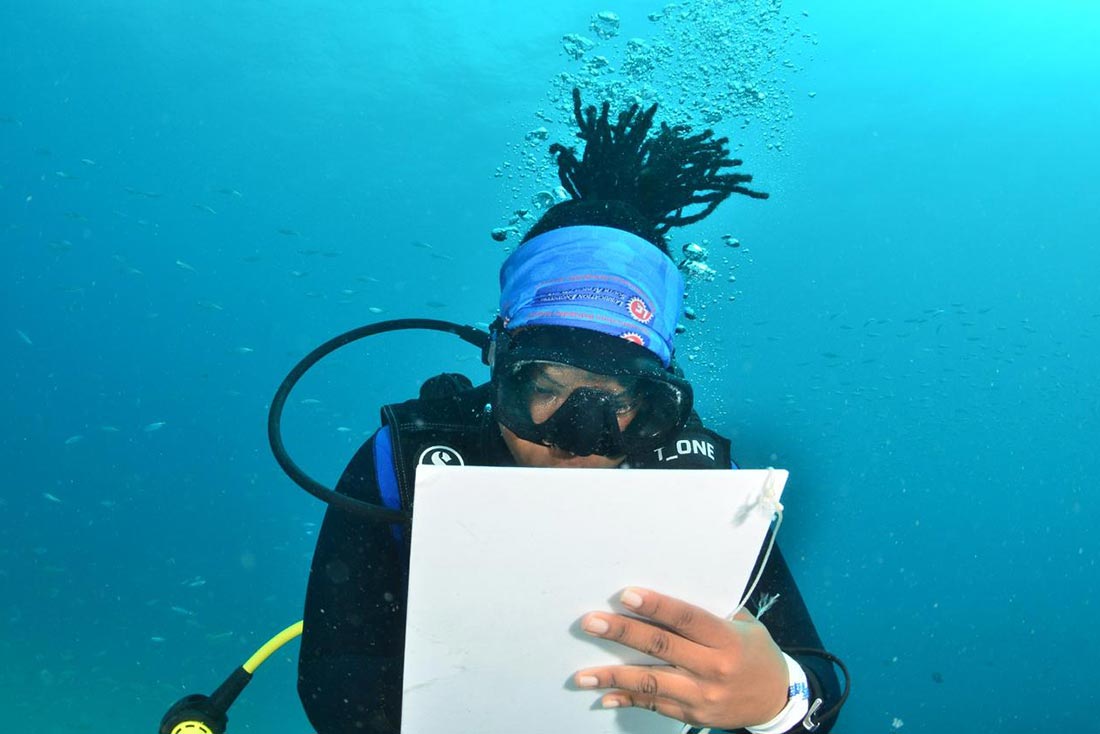

Mamy Florentin and Ratafita (Tafita) Migdal’Elah are our team’s skilled field assistants who follow the lemur groups in Vohibe. Typically, researchers use collars and tags for lemur identification. However, after facing some technical difficulties with this approach, Mamy and Tafita used natural marks and fur color to identify each lemur instead (which is no easy task!). Mamy and Tafita systematically collect GPS waypoints every 15 minutes and update our records with group composition and dynamics. They also note details about health and major events (e.g., reproduction or predation).

We found that of the four diademed sifaka babies born in three groups during the July through August 2023 birthing season, three are still alive, and one has disappeared. Unfortunately, a one-month-old baby born in July 2024 died due to infanticide. We also recorded the birth of three pairs of black-and-white ruffed lemur twins in two groups between October and November 2023 (which was great news because we did not record any births in 2022).

The field assistants continue to monitor all the lemur groups and report their results directly to the Ph.D. students. In the process, they have also become excellent wildlife photographers!

Battling Illegal Activities with Conservation Education – The Challenge for the Future

Our reforestation success in Vohibe is exciting, but our work is not done. Patrollers still find signs of illegal activity within the forested areas from “tavy” (the local term for slash-and-burn agriculture) and forest-and-river destroying gold mines. Changing people’s behaviors is probably the most difficult aspect since it requires time and perseverance.

Outreach and engagement activities for locals living around Vohibe are fundamental for preventing and reducing illegal activities within the protected area. Lesabotsy, our outreach conservation ambassador, held events and meetings focused on reducing lemur hunting in eight villages—three more than originally planned. The outreach activities appeared successful, as there have been fewer reports of hunting evidence than before the lessons occurred. However, there is still a need to extend outreach to include other topics and increase the involvement of women.

Each October, the MBG Madagascar program organizes a biodiversity festival in the main village of Ambalabe. We always look forward to this entertaining event because it includes a carnival, dances, and fun educational activities. In addition, the festival is a great opportunity for people of all ages to learn about the incredible and unique biodiversity of Malagasy rainforests and the importance of preserving it.